Page 2 of 3

Gear Conversion

Well, this one is really quite horrible. I don't know when it was done, but it certainly

was no earlier than the mid 1970s, because that's when the guitar was made. It takes

a bit of doing to remember that we really have no way of knowing the motivation or

reason for the work. It's still important to recognize that we don't know why, and

since we can't go back, we must forgive it.

We often decry the loss of "originality" when replacing tuning machines,

but such replacement usually at least results in an instrument that works better.

This one, with the increased downward pressure on the nut, actually doesn't work

well at all:

I find this modification somewhat less forgivable than those coversions we see which

were made during the "dark ages" of low guitar popularity. Grover Rotomatic

or Schaller tuners could be had for less than 25 bucks, would have worked well, and

would have been easy to install.

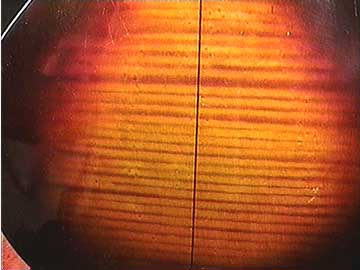

Faux Wood Grain

I have to show you two more pictures of this fine old archtop guitar. It's really

quite a piece of work. The top and back are made of fine solid birdseye maple. But

check out the wonderful finish:

Here the back is spray painted to simulate curly fiddle back maple grain. It's not

a bad job for a production guitar; it's just a shame that they didn't simply let

the birdseyes carry the show!

The top is even more amazing. Same tightly figured birdseye maple here, but this

time they've painted it to look like spruce:

Gibson Mandolin Beautification Project

This is a classic Gibson style A mandolin from about 1915:

And, it has been richly incised to create a European flavor. Unfortunately, it's

not the sort of work that can be easily undone.

Conversions

Here are three skeletons from my closet:

At the top, it's a neck from a 1930s Gibson F-7. MOre than twenty years ago

I was asked to convert this instrument from the F-7 short neck to the F-5 long

neck style. Most everyone would agree that the conversion successfully upgraded

the instrument to a much more playable and better sounding mandolin. These days,

however, we all agree that the collector value is greater than the "musical

value" so it's not a wise thing to do.

The middle neck was one I removed from a Martin OM-18P, a plectrum 4-string

guitar. I reshaped and transplanted a 1940s vintage D-18 neck onto that instrument,

converting it to a regular six-string guitar.

Both of these jobs were done a long time ago and represented the current state

of the art thinking at the time, so I feel I have nothing to apologize for.

These necks do serve as a reminder of days past.

The bottom neck is a tenor banjo neck from which I salvaged the peghead overlay

in order to make a five string replica neck. I acquired the neck, broken off

at the heel, without the rest of the banjo. In 1974, I bandsawed off the peghead

veneer as I had on other occasions to lend a bit of "authenticity"

to my replica neck. That was at the time considered the proper thing to do,

both to save effort in inlay work, and to capture a bit of originality. Most

of the necks we salvaged in this way in the 1960s were not damaged, they were

just four string necks, and not considered valuable at the time. These days,

it's considered more appropriate to reproduce the peghead inlay, and keep the

tenor neck intact. It seems obvious now, but it didn't then.

If you'd like to see the results of the five string conversion, click here for

some photos of the Washburn banjo, which I still have after 25 years.

And, here's another old Washburn banjo. This one dates from about 1900, and

appears to be a short neck tenor, with an inlay at an unusual position, namely

the second fret:

A closer examination reveals that it was originally an elegant open back five

string banjo that was skillfully cut down to make it into a short 15-fret tenor

at a time (probably the 1920s) when the short neck tenor was a popular melody

instrument.

No trace of the original fifth peg remains, and that second fret inlay was originally

at the seventh fret. The only thing I know for sure is we have no place asking,

"What were they thinking?" or "How could they have done

that?" That was then, this is now. . .

More

1

2

3

Back to Index Page