Checking Neck Angle

© Frank Ford, 11/26/99; Photos by FF, 9/10/99

With time and the relentless pull of the strings, a flattop guitar is bound to undergo some changes. Slowly, the body changes shape. Not unlike some of us old guitar pickers, the instrument begins to show its age. The belly starts to protrude a little, the shoulders bend, and the neck pulls forward a bit.

OK, I'll stop with that analogy.

A guitar can be thought of as being almost like a living system, though.

Under the strain of six strings tuned to pitch, the upper "shoulder" of the body rotates forward just a bit. The area around the soundhole dips downward a little, and the top starts to "dome" around and behind the bridge. The back of the instrument may flatten a little, effectively becoming a trifle longer in the process. Each of these phenomena contribute toward the "forward" rotation of the neck block and neck. Even though the neck remains straight through its length, it begins to "aim" toward a lower position on the bridge.

I'd like to reiterate one point I made in the article about adjusting truss rods. Truss rods have no influence on neck angle. The truss rod helps to keep the neck straight, and controls neck relief from the nut to about two frets from the body. The truss rod can only affect the flexible "shaft" portion of the neck. Its effect ends in the area where the neck becomes thicker at the heel, even if the truss rod extends further.

I believe that virtually all traditional flat top guitars will eventually show the need for neck resetting. Generally, the lighter built guitars will need to undergo the reset operation sooner than heavier ones. For example Martin guitars seem to be on a 20- or 25-year cycle, on average. After the neck reset has been performed, the same forces of string tension will continue to change the body, and the neck will need to be reset again. I really don't know what the eventual outcome will be. Will there come a time when the instrument stabilizes completely, or collapses completely? So far, the population of steel string flat top guitars is not old enough to answer that question. Certainly, most well made guitars will easily outlast their owners. . .

With the slow rotation of the neck in relation to the top, the most obvious symptom is a change in string height, or action, especially in the higher fret positions. In fact, if you know what you're doing, you can often use the string height as the best indication of whether a guitar needs to have its neck reset.

I use three methods to determine if there's a neck angle problem. I'll generally use the third one, just in the course of giving the guitar a general looking over. Bear in mind that first, I'll make sure that the truss rod is correctly adjusted and that the neck is appropriately straight.

Sighting down the fingerboard, I'll line up the corners of the frets and see if there's an apparent bend in the fingerboard near where the neck joins the body:

The neck is clearly too thick in that area to bend, but if the neck is out of alignment with the body, there may be an apparent upward bend of the end of the fingerboard. Often, guitars with neck angle problems may show no such bend, because the end of the fingerboard may dip downward at the soundhole, either as part of the original construction or as a result of the neck pulling forward and taking the fingerboard and top along with it. But the appearance of a bend right at the body is frequently a sign of neck angle trouble.

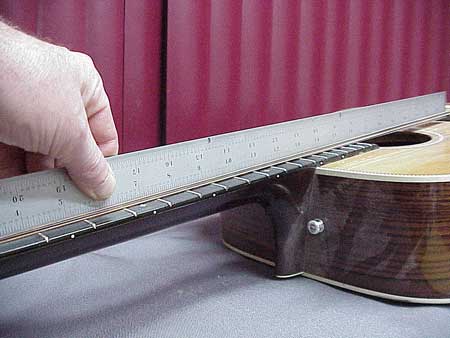

If the fingerboard is reasonably straight, end to end, I'll lay a 24" straightedge on top of the frets like this:

I can't use the straightedge if the fingerboard bends because it won't "read" the tops of the frets accurately to give me a sense of the neck angle.

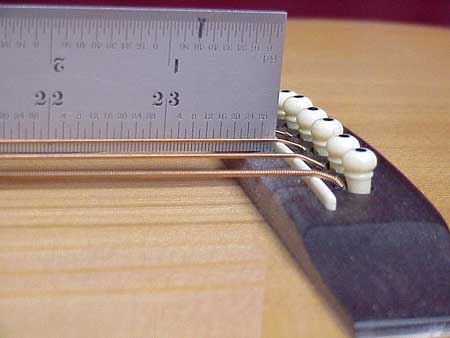

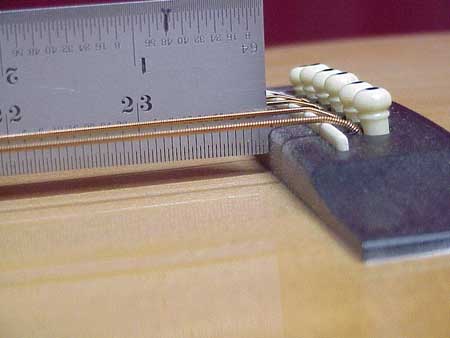

Now, pushing the straightedge toward the bridge I'd like to see it "land" right on top of the wooden part of the bridge:

This is the way most guitars are built, and if the straightedge lays right on the top of the bridge, and right on top of the frets along the length of the neck, then I know the neck angle is just right.

Unfortunately, this guitar shows a clear need for neck angle work:

The straightedge touches the bridge only 1/8" from the top of the guitar.

This diagnostic method is very clear, but it doesn't account for the thickness of the bridge. If the bridge had been cut low in an effort to forestall neck angle work, then the straightedge might land right where it belongs on top of the bridge, but the neck angle may be less than ideal. I could measure the height of the bridge (not including the saddle) and hope that it's somewhere between 5/16" and 3/8," or I could use an even simpler method to check neck angle.

Here's a simple method for checking neck angle that doesn't depend on fret or fingerboard condition, or bridge height.

First, check to see that the neck is straight, then take note of the action at the twelfth fret. Presuming that the action is reasonable, say, between 3/32" and 4/32" between the bottom of the low E string and the top of the twelfth fret, then simply measure the string height in front of the bridge:

If there's about 1/2" between the low E and the top, then the neck angle is just about right:

If there's less than 3/8" between the string and the top, then there's neck angle trouble:

If the strings are this close to the top, it means that the saddle and/or bridge have been seriously lowered to compensate for a "shallow" neck angle.

If I don't have a scale handy, I can easily estimate the difference between 1/2" and 3/8" visually, and by checking how my finger fits under the "E" string:

Here are some more indicators of neck angle problems:

The action is really high, over 4/32"

AND the saddle is VERY low:

Of course, there is such a thing as a "reverse" neck angle problem, usually a result of poor manufacture or repair. IF the action is way too low, and the saddle is really high, it usually means that the neck angle was set too far "back."

This high saddle is OK, but it certainly can't stand the strain of being raised, so if the action is not too low, then the neck angle is probably just right:

If, however, the action is super low, then I'd want to talk about reset the neck in the "forward" direction.